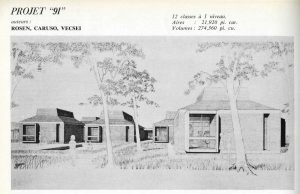

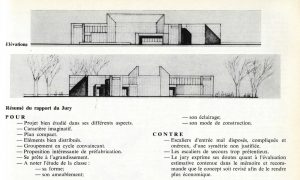

“Concours pour écoles primaires, Québec, 1964”. Top image, project by Rosen, Caruso, Vecsei, bottom image project by Melvin Charney (see Canadian Competitions Catalogue)

Organized by the government of Quebec, the “provincial architecture competition for elementary school” was launched in the midst of the “quiet revolution”, under the watchful eye of the religious authorities hitherto in charge of education. Traditional schools had to make way for new spatial organizations and a vast educational project began with the publication of the now famous “Parent Report” (1964). What is felt today as the sad memory of the so-called “prefabricated” places of education is probably not what the organizers had foreseen in terms of the renewal of school architecture. The fact remains that the analysis of the jury report shows the disproportionate importance of two criteria that converged on the same principle: identifying new standard plans and verifying that they could accommodate the industrialization of construction.

Nearly sixty years after its publication, the “Parent Report” is today a historical document, sometimes obsolete. However, at the time of its publication, the report directed by Alphonse-Marie Parent, in 5 volumes of nearly 1500 pages, was published by the Royal Commission on Education between 1963 and 1964 and was a milestone in the “quiet revolution” in Quebec. It proposed, no more and no less, the creation of a Ministry of Education, compulsory schooling until the age of 16, the creation of “CEGEPs” and, in general, the democratization of higher education. In other words, we are moving from religious education to education for all, as Claude Corbo, former rector of the Université du Québec à Montréal, wrote in 2002.

It is in this vast educational site in Quebec that the “provincial architecture competition for elementary schools” was organized as early as 1964. Its goal was to propose new concepts for elementary schools and was looking for “model plans”. The program – which will appear summary in terms of contemporary “functional and technical programs” (FTP) – included: twelve classrooms, including one kindergarten class, a library, a dining room, a gathering space as well as changing rooms and staff quarters. The clientelism that the academic authorities are sometimes criticized for was already included in the “list of premises”: “Immediate environment: Taking into account the different clienteles: schoolchildren, faculty and the general public. Provide for each of these clienteles to have access to the school either on foot or in motor vehicles. »

Chaired by the architect Jean Damphouse, the jury was composed of the architects Raymond Affleck, Jean Paul Carlhian, Alfred Roth, Victor Prus, and the “designer” (sic in the publications) François Lamy. It should be noted that the jury did not include an expert in education or a representative of the school milieu, but was composed of an industrial designer and five architects, including the famous Alfred Roth, considered the Swiss expert for having contributed to the revival of educational architecture in the 1950s. Assistant to Le Corbusier and then collaborator of Marcel Breuer, representative of the “Neues Bauen” movement, the modernist “new objectivity”, Alfred Roth settled in Zurich and worked regularly with Alvar Aalto.

In other words, the program of the 1964 “Canadian” competition must have seemed elementary to the Swiss modernist. It was asked to take into account the immediate environment, without specifying which one, and three types of classrooms were distinguished according to whether they accommodated 30, 33 or 35 students. It was suggested, for example, that for classrooms of 35 students, during a teaching period, students would be required to use three different methods of work: work in homogeneous groups, work in sub-groups for research, and individual work for further training.

Equipped with such pedagogical refinement, the jury selected 14 projects, according to particularly deterministic criteria, including those of Melvin Charney, Jean Michaud, from the Rosen, Caruso, Vecsei consortium and the Ouellet, Reeves, Guité, Alain consortium. The description of the fourteen projects and the jury’s comments appeared in the April 1965 issue of Architecture-Bâtiment-Construction magazine, and while black and white printed graphic documents are sometimes difficult to read today, the dualism of the jury’s comments is clearly displayed in two columns of lapidary statements listing the “pros” and “cons”.

For one project, the jury emphasized that “its universal character is suitable for possible prefabrication” because its “plan is clear and well-disciplined”, for another, that it “lends itself to expansion” or that “the plan is well organized”, that the “project lends itself to expansion possibilities” or that the “good natural lighting of the classrooms by means of skylights is well designed”. Melvin Charney’s project is credited as an “interesting prefabrication proposal” whose fire stairs are described as “pretentious”. The “difference in levels between the cafeteria and the common room” of the beautiful modernist project by St-Gelais, Tremblay and Tremblay is deplored, while the extreme refinement of the project by Rosen, Caruso, Vecsei, a subtle and skillful mix of borrowings from the architectures of Louis Kahn and Aldo Van Eyck, is considered a “project well studied in all its aspects” but whose “abundance of exterior walls and excess circulation surfaces” leads to fears of “high construction costs”.

The comparative publication of the competition results in April 1965, in the only specialized Quebec magazine at the time, Architecture – Bâtiment – Construction, had a great impact on the imagination of architects for more than a decade, with sometimes questionable results.

There were only a few competitions in the field of education in Canada in the 1960s and 1970s, mainly for universities, and it was not until the late 1980s and especially the 1990s that the aging building stock required new consultations and reflections. These were strongly encouraged, this time, by the numerous studies, mainly sociological, carried out in particular in the Swiss and French contexts. However, in a characteristic way and contrary to the importance of competitions dedicated to school buildings in all European countries, one can legitimately be surprised that schools are not considered as architectural issues in North America.

More on this competition on the Canadian Competitions Catalogue

Jean-Pierre Chupin