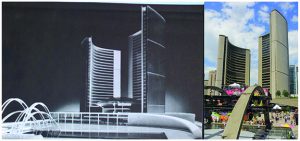

The competition for the Toronto City Hall was won in 1958 by Viljo Revell (On the left the model produced for the competition, on the right photography taken by the author in 2015)

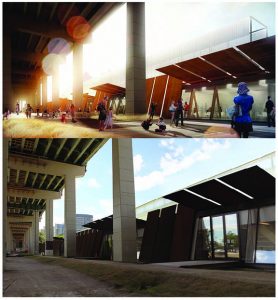

The Fort York Visitor Centre as a competition project won in 2009 by Patkau Architects and Kearns Mancini Architects (Top, a digital model produced during the competition, below a photo taken by the author in 2015)

Should we be able to measure the gap between the promise of the image produced during a competition (from a physical or digital model) and a photograph of the awarded building taken from similar angles several years later? In other words: How much should the constructed building look like the model that anticipated its appearance?

Each architectural model falls into the broad scientific category of “models”, while each model is itself a “figure to reproduce” (1). At the crossroads of these two principles, the architectural model should be “a reduced architecture to reproduce” according to varying degrees of fidelity. A designer is always more or less aware of the gap separating these representations from the expected built reality. On the other hand, in competition situations, the model is also a tool for explaining the project or even an argument to win the jury’s approval, which is not necessarily prepared to consider these artifacts with the same critical distance as their designers.

In order to measure the gap between the competition models and the building photographs that they originally represented, it is enlightening to compare two winning competition projects 60 years apart in Toronto: they have been awarded prizes of excellence, confirming their exemplary value and making them “role models”.

The competition for Toronto City Hall was won in 1958 by Vilijo Revell, while the building won an Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) Landmark Award in 1998. The Fort York Visitor Center, the result of a competition won in 2009 by Patkau Architects and Kearns Mancini Architects, was quickly awarded the Canadian Architect Award of Excellence in 2011, followed a few years later by a City of Toronto Urban Design Award and an Honourable Mention for Design Excellence from the Ontario Association of Architects in 2015, just prior to its consecration with a Governor General’s Medal in 2018.

The models of the Toronto City Hall made during the second stage of the competition were required for all competitors: and we know these famous images showing hundreds of models carefully arranged on huge tables so that the jury can examine them. If the photo of the competition model resembles the built project we photographed in 2015, there are several notable differences. The number of arches facing the tower has gone from 3 to 5 and their shapes have been simplified. They have also slid east of the body of water, which was halved. The division of the main building’s floors, which is perfectly regular on the model photographs gives way to wider intermediate and final levels. Finally, the gables of the two towers are less glazed than what the model displayed and thus the project at the competition stage. These differences appear minimal when we recall that this model was produced 7 years before the inauguration of the building in 1965.

The model produced by the winning team during the competition for the Fort York Visitor Center is only presented through the digital images it has produced. If the latter seek to anticipate the photographic representation pursuing objectives like the photograph of the model carried out in the context of the competition for City Hall, it must be kept in mind that these images have certainly been subjected to retouching. In addition to the lack of public and the tired grass banal witnesses of reality, the building’s photography in 2015 also appears very similar to the computer-generated image from a digital modelling from the competition. The translucent volume on the roof appears higher on the image than it will eventually be, while the glazing seems less transparent than announced by the perspective drawing: the difference between the two images of the project is small. The size of certain openings has changed somewhat and the number of corten steel panels has been modified accordingly, but the promised project is very close to the building that will finally be delivered 5 years later, in 2014.

Through these summary comparisons, it appears that the change of support of the models, namely, of the very nature of the architectural models does not necessarily seem to modify the distance that separates the object from the building which it represents: the two cases mentioned admit similarities and differences of the same order. Although the summary comparison of these two projects cannot support any generalization, the models can anticipate the realization and this leaves little doubt about the purpose of the mediations, which both deserve the name of “reduced architecture to reproduce”.

It may be objected that the similarity observed in these diachronic confrontations of perspective views is an exception and that few buildings can boast of always being so close to the original project. Nevertheless, it is clear that these two buildings whose architectural excellence was recognized have reproduced the same feat 60 years apart. One can wonder if this proximity is one of the marks of architectural excellence? Therefore, a good project, according to its etymology, would be a building that would have been precisely “thrown forward” by its model, that is to say, perfectly anticipated.

Unlike models of design, engineering or exhibition that could be respectively named exploratory models, predictive models and descriptive model, the models of competitions, whether they be virtual or physical, are the real models of the project (1) available to architects. Paradoxically, by confusing the latter, they are often the ones who make their own models lie.

Each architectural model falls into the broad scientific category of “models”, while each model is itself a “figure to reproduce”. At the crossroads of these two principles, the architectural model should be “a reduced architecture to reproduce” according to varying degrees of fidelity. A designer is always more or less aware of the gap separating these representations from the expected built reality. On the other hand, in competition situations, the model is also a tool for explaining the project or even an argument to win the jury’s approval, which is not necessarily prepared to consider these artifacts with the same critical distance as their designers.

In order to measure the gap between the competition models and the building photographs that they originally represented, it is enlightening to compare two winning competition projects 60 years apart in Toronto: they have been awarded prizes of excellence, confirming their exemplary value and making them “role models”.

The competition for Toronto City Hall was won in 1958 by Vilijo Revell, while the building won an Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) Landmark Award in 1998. The Fort York Visitor Center, the result of a competition won in 2009 by Patkau Architects and Kearns Mancini Architects, was quickly awarded the Canadian Architect Award of Excellence in 2011, followed a few years later by a City of Toronto Urban Design Award and an Honourable Mention for Design Excellence from the Ontario Association of Architects in 2015, just prior to its consecration with a Governor General’s Medal in 2018.

The models of the Toronto City Hall made during the second stage of the competition were required for all competitors: and we know these famous images showing hundreds of models carefully arranged on huge tables so that the jury can examine them. If the photo of the competition model resembles the built project we photographed in 2015, there are several notable differences. The number of arches facing the tower has gone from 3 to 5 and their shapes have been simplified. They have also slid east of the body of water, which was halved. The division of the main building’s floors, which is perfectly regular on the model photographs gives way to wider intermediate and final levels. Finally, the gables of the two towers are less glazed than what the model displayed and thus the project at the competition stage. These differences appear minimal when we recall that this model was produced 7 years before the inauguration of the building in 1965.

The model produced by the winning team during the competition for the Fort York Visitor Center is only presented through the digital images it has produced. If the latter seek to anticipate the photographic representation pursuing objectives like the photograph of the model carried out in the context of the competition for City Hall, it must be kept in mind that these images have certainly been subjected to retouching. In addition to the lack of public and the tired grass banal witnesses of reality, the building’s photography in 2015 also appears very similar to the computer-generated image from a digital modelling from the competition. The translucent volume on the roof appears higher on the image than it will eventually be, while the glazing seems less transparent than announced by the perspective drawing: the difference between the two images of the project is small. The size of certain openings has changed somewhat and the number of corten steel panels has been modified accordingly, but the promised project is very close to the building that will finally be delivered 5 years later, in 2014.

Through these summary comparisons, it appears that the change of support of the models, namely, of the very nature of the architectural models does not necessarily seem to modify the distance that separates the object from the building which it represents: the two cases mentioned admit similarities and differences of the same order. Although the summary comparison of these two projects cannot support any generalization, the models can anticipate the realization and this leaves little doubt about the purpose of the mediations, which both deserve the name of “reduced architecture to reproduce”.

It may be objected that the similarity observed in these diachronic confrontations of perspective views is an exception and that few buildings can boast of always being so close to the original project. Nevertheless, it is clear that these two buildings whose architectural excellence was recognized have reproduced the same feat 60 years apart. One can wonder if this proximity is one of the marks of architectural excellence? Therefore, a good project, according to its etymology, would be a building that would have been precisely “thrown forward” by its model, that is to say, perfectly anticipated.

Unlike models of design, engineering or exhibition that could be respectively named exploratory models, predictive models and descriptive model, the models of competitions, whether they be virtual or physical, are the real models of the project (2) available to architects. Paradoxically, by confusing the latter, they are often the ones who make their own models lie.

Aurélien Catros

(1) – Rey, Alain. (Éd.), Dictionnaire historique de la langue française, Paris, Le Robert, 1998.

(2) – What Marcial Echenique named in the 1970s “planning models”. Echenique, Marcial, Models: A Discussion, Cambridge, University of Cambridge, 1968.